Need for Certainty

Need for Certainty

The need for certainty guides much of human behavior and is one of the psychological reasons for belief in idols, political leaders, and computer predictions.

The evolving spread of the novel coronavirus has filled many of us with doubt as we find ourselves confronted with choices we must quickly make. Some of these choices can be very painful, like my own decision not to travel overseas to be with my critically ill parent who entered the intensive care unit a week ago — the complexity of this situation exceeds the capacity of words. But worse than pain is indifference.

The local and global situation we all face calls upon our courage to think for ourselves and to make decisions based on our full intellectual and emotional commitment to life. Each individual needs to understand his or her situation, see the alternatives, and then decide. We all must care and use our reason as we relate and respond to the reality with which we are dealing.

How Social Distancing Flattens the Epidemic Curve

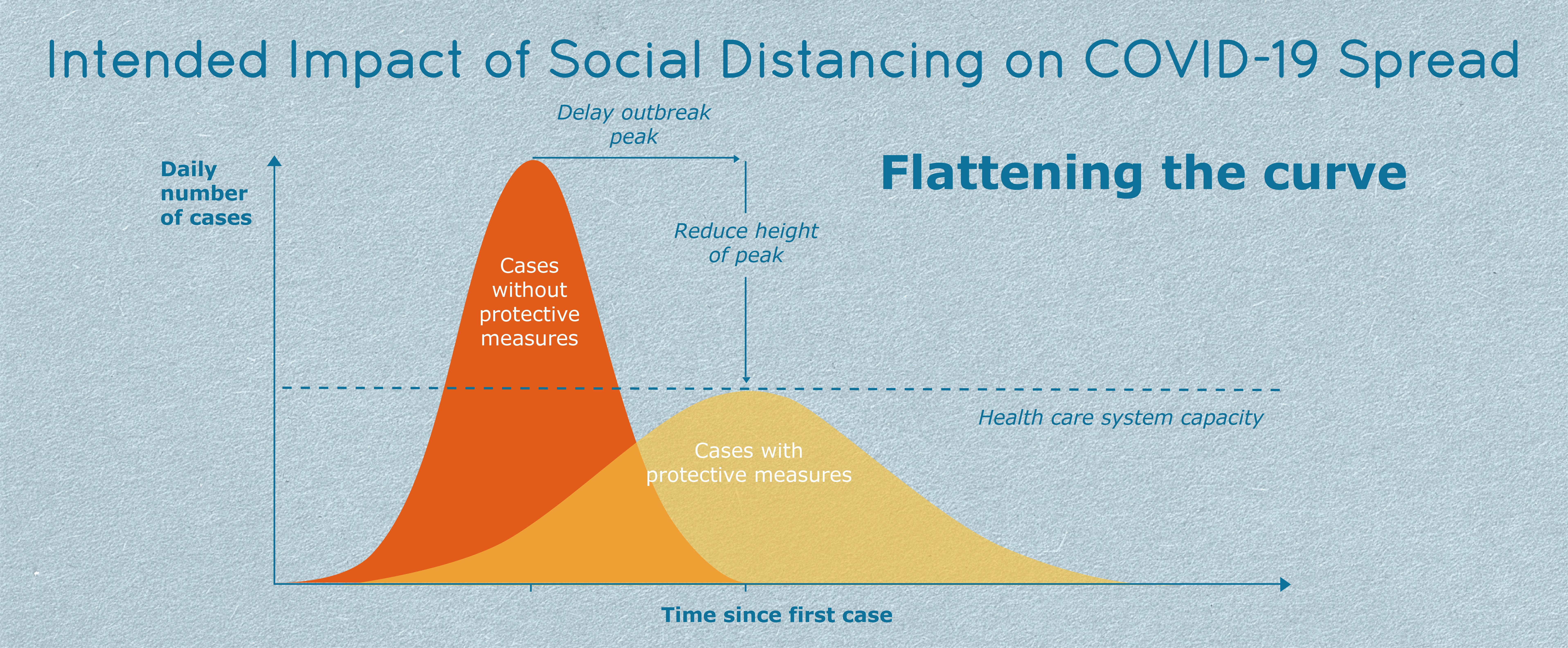

The spread of the novel coronavirus through a population can be visualized by epidemic curves, like those in the above graphic. On a given day the height of the curve corresponds to how many new people are known to have developed the disease. The area under the curve is a measure of the total number of people who developed the disease during its course of spread through the population.

It is not possible on any day to know with absolute certainty what the epidemic curve of the novel coronavirus will look like in the U.S. or another country in which the spread is still active. We can only make predictions based on how the spread has behaved so far, and what effect we think individual behaviors and government policies to contain or mitigate the spread might have.

The two curves in the above graphic are different in two key ways — they peak at different times, and they grow at different rates. The curve with the higher peak is growing steadily by a fixed higher percentage than the flatter curve with the lower peak. Last week, the number of confirmed cases in the U.S. was growing by 30% to 40%. If you follow the number of cases and find it to be doubling every fixed number of days, the growth is exponential.

The flatter curve rises more slowly, meaning the virus is spreading more slowly, and it also peaks at a later time point, stretching the course of the pandemic over a longer period of time. This is critical, not only because the total number of people infected over the course of the pandemic is potentially lower in the scenario of the flatter curve, but most importantly because the number of ill people who would require hospitalization would not outstrip the health care system’s current capacity to care for them.

There are a lot of things we do not yet know about the novel coronavirus and the disease it causes, COVID-19, but some things are known:

“Individual behaviour will be crucial to control the spread of COVID-19. Personal, rather than government action, in western democracies might be the most important issue. Early self-isolation, seeking medical advice remotely unless symptoms are severe, and social distancing are key.”

(Lancet, March 9, 2020)

What is social distancing? It is more than maintaining a distance of a certain number of feet from those sneezing and coughing. Dr. Asaf Bitton of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, published a very clear guide to the role we all play in social distancing and how to practice it to help flatten the curve of this pandemic.

Social distancing is challenging to both initiate and maintain, but until we have medication for or vaccine against the novel coronavirus, it could be the most effective way to both flatten the curve and reduce the severity of the pandemic for the elderly, those with underlying health conditions, and for health care workers and first responders on the front lines. It is a social responsibility along with being an individual protection.

Be safe and be well,

Aliaa